Through a cord of publicly available submissions, press statements, and various media reports, In this article you will get to know about the political evolution of the data protection ecosystem in India, and how this has and will constantly affect the legislative and policy developments. The Personal Data Protection Bill, or the PDP Bill, has been listed for the introduction recently in Parliament. The Bill has long-reaching consequences for political economy, private industry, and India’s strategic camp. The governance of technology is inherently political and the Government of India has constantly stressed the requirements for strategic autonomy in designing out its “Data Sovereignty Vision.” Entities within the departmental machinery, along with some doyens of Indian industry, have been proactive in painting India’s cyber policy vision as one that would protect against continued “data imperialism” by foreign technology players, and assure that the data generated by Indian citizens is utilized for their progress.

Along the way, there have been some flaws in the instruments responsible for the realization of the vision, and this has been highlighted continuously by civil society and academics. Eventually, the relative shortage of public information about the interests of different lobbying groups has prevented us from conducting a comprehensive factual survey to appraise how interest groups have aligned on various sides of the lobbying battle; as has been done in the case of the evolution of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

What is the Background to the PDP Bill?

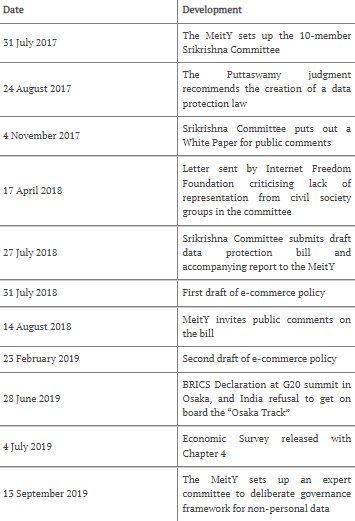

The process towards the updated version of the data protection law began in 2017. However, despite repeated statements that India will soon have this law in place, we have seen little movement. In 2017 during the Supreme Court hearings in the referral matter before the constitutional bench to clear the judicial uncertainty around the existence of the right to privacy in KS Puttaswamy and Anr v Union of India and Ors 2017 (the Puttaswamy judgment), the Government of India announced the setting up of an expert committee to frame India’s data protection law (Agarwal 2017). The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) formed a 10-member committee led by retired Supreme Court judge BN Srikrishna. This was not the first exercise towards the creation of India’s data protection law. In fact, over the last decade, there have been other such efforts and bills. In 2012, Justice A P Shah had led another committee of experts and provided detailed recommendations towards the creation of a data protection regulation (Agarwal 2017). Before the MeitY, the Department of Personnel and Training had been the nodal authority working on privacy legislation, and there were at least two different drafts, one from 2011 and another from 2014 (Hickok 2014) that were produced.

The composition and processes followed by the committee led by Justice B N Srikrishna attracted some criticism. An open letter sent by advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation, which also led parallel efforts called #SaveOurPrivacy—a movement in support of a model draft law—criticized the composition of the committee citing lack of representation from civil society, and instead suggested having representation from those who “had been votaries of the Aadhaar infrastructure, and so may not be a position to objectively and critically analyze the Aadhaar infrastructure from the standpoint of Citizen’s Data Security and Privacy.” Another criticism of the functioning of the committee was the lack of transparency (Deep 2018). The MeitY stressed that the submissions were “confidential” and “not available for public dissemination,” unless the entities who submitted responses provided consent.

Development of the Data Protection Ecosystem

On 27 July 2018, the Srikrishna Committee submitted a draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018 to the MeitY, along with a report titled “A Free and Fair Digital Economy” (Srikrishna Committee 2018) On 14 August, the MeitY invited public comments on the bill to be received in 20 days till 5 September, a period that was later extended until 30 September. Even though there were reportedly over 600 submissions, the MeitY refused to make this public.

In 2019, two iterations of the draft national e-commerce policy (the second one christened with the theme “India’s Data for India’s Development”) were put out by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) under the Ministry of Commerce. These endorsed certain provisions in the draft PDP Bill, but also fostered a lack of clarity regarding concepts such as “community data”—data is viewed as a “societal commons” or “natural resource”—held by an unidentified (presumably national) community (Basu 2019). While ambitious in its vision, the policy failed to highlight any meaningful ways in which “community data” can be utilized by the government or a clear demarcation between personal and non-personal data. To complicate matters further, Chapter 4 of the Economic Survey released by the Ministry of Finance in July 2019 conceptualized data as a “public good” once data sets are obscurity without any mention of data protection, barring a passing note on respecting privacy norms. Further, the end of the chapter appeared to suggest that this data can be sold to public firms without clarifying whether this means foreign or domestic firms. This defines the essence of a public good, which is defined as being non-excludable and non-emulous.

In September 2019, the Meity also set up an expert committee to facilitate the recommendations that will not affect the PDP Bill; they will likely deliver as the structure for the governance of any data confidential as “non-personal.”

What are the Major Issues, Engagements, and Conflicting Interests?

Data Localizations: The data localization provisions included in Sections 40 and 41 of the draft PDP Bill were probably the most disputed and generated heated debate. The provisions were an addition to an abundance of notifications and policies across ministries that had assigned localization in some form. While there were several reasons for data localization provided in the report of the Srikrishna Committee, two stood out in particular. Initial is the cumbersome and time-consuming process that the law enforcement agencies have to go through criminal researches to access stored in the United States (US), which has been, according to law-enforcement officials, a major fetter to the successful completion of criminal investigations (since 2016). Second, data localization is viewed as a means of combating “data colonialism,” which refers to the extractive economic models used by Western (largely, US) companies to use data generated in developing countries like India to consolidate their global market power.

The debate on data localization is certainly driven by anticipated economic interests, in some of the stakeholders. Probably paper analyzed the reverts of 51 stakeholders to India’s localization gambit. Stakeholders arguing for data localization include large Indian corporations such as Reliance and PhonePe, which can build their data centers in India, or pay for data to be stored on Indian servers. Mukesh Ambani, Chairman of Reliance Industries, has been a vocal proponent of data localization, using the government’s “data colonization” narrative (Economic Times 2018). Chinese players like Alibaba and Xilinx have also taken pro-localization stances, possibly because some of them have already set up data centers in India (Variyar 2018).

On the other side, industry association, including the Internet and Mobile Association of Indian and the National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM), also stands up against data localization, announcing the cost to startups and consequent problem for India’s innovation ecosystem. Various foreign technology players such as Google, Microsoft, Facebook have continuously pushed back against data localization.

Governing Personal and Non-Personal Data: The PDP Bill defines personal information as any “data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable, also have regards to any characteristic, attribute, or any other features, or the combinations of such features with any other data.” This intent is reflected in the setting up of a new committee. However, one should expect further clarity and coordination as a result of these deliberations, especially since two crucial ministries—the MeitY and Ministry of Commerce (through the DPIIT)—are on board, along with expert representation from both the civil society and private sector.

The Government’s Use of Data: The PDP Bill contemplates a drastic change in data collection and processing practices in India. So far, both the private sector and the state have operated in a largely unregulated space, where they do not have to worry about checks and balances and processes to protect the privacy interests of the citizens. There is obvious discomfort about the nature and form of regulation being introduced. The state’s agenda has, to some extent, already seen significant concessions in the language of the bill.

Finishing Up!!

Instead of some steps towards a data protection regulation in the last few decades, the Indian government has failed to pass the law. Finally, non-personal data has found its way into the text of the revised bill. Sticking to its grand vision of ensuring that India’s data is used for India’s development, the government included a provision clarifying its power to frame any policies that would benefit India’s digital economy, so long as it did not concern personal data. It goes on to state that, in consultation with the Data Protection Authority (DPA), it can direct any data fiduciary to hand over anonymized personal data or other “non-personal data” for “evidence-based policymaking” with no clarity on what evidence-based policy-making might entail.

As the Joint Parliamentary Committee commences its deliberations, we do not doubt that the interests identified in this article will continue to shape the contours of the bill. The key question is whether the final text will be able to grapple with the politics of the multiple interests shaping this bill while still championing and prioritizing citizen rights.